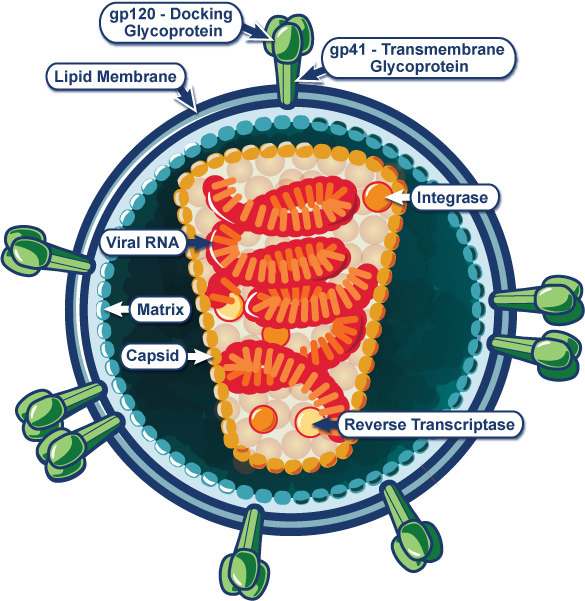

In this schematic of the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), the glycoproteins gp41 and gp120 are the base and tip, respectively, of the “spikes” protruding from the membrane. Credit: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

The saga of Dong-Pyou Han and his research misconduct continues.

Late last week, Iowa State University responded to my request for a report the university sent to the Office of Research Integrity (ORI) at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

The documents include Han’s signed admission of how he spiked blood samples to make it appear rabbits developed antibodies to HIV, the AIDS virus.

Michael Cho, the project’s lead researcher, reported the suspected misconduct one year ago this week, and after an investigation stretching into August, pegged Han as the likely culprit. He resigned in October.

Han is the only researcher suspected in the fraud.

The Des Moines Register’s Tony Leys also received the documents – including emails concerning the investigation, which I did not request – and wrote a piece Thursday night. Another piece on Friday quotes Arthur Caplan, the go-to source when journalists need a comment on bioethics.

Leys’ initial story covers Han’s grammatically clumsy mea culpa but omits many details – including what appears to be his rationale for the whole fraud.

Han, who came to ISU with Cho from Case Western Reserve University (CWRU), signed an agreement with ORI banning him from participating in federally funded research for three years from Nov. 25, 2013. (I’m not sure why Leys’ latest stories say five years.)

Emails the Register obtained hint that Han may have returned to his native South Korea. When you read his statements, bear in mind that English is his second language.

In his admission (pages 16 and 17 in the document below), Han says he’s ashamed about his misconduct and that he was “foolish, coward, and not frank. My misconduct is not done in order to hurt someone. All cause by my foolishness and are my faulty and responsibility.”

But in the confession, which is admittedly difficult to parse thanks to the poor English, Han also seems to claim the fraud started when he tried to hide an error. The documents (from which ISU cut the names of most other researchers and institutions) also say Han first spiked samples in 2009, while he was still at CWRU.

“The problem starts from the first samples that I sent [redacted] on 8/11/09. I found the samples were something wrong later,” Han writes. He thought the samples were contaminated with human sera (blood or blood products used to provide immunity) capable of neutralizing HIV – what the documents call neutralizing activity (NA) or broadly neutralizing activity.

“Because I worked the rabbits sera and human sera … at the same time though I do not remember the date, may be some samples were contaminated (mixed),” Han writes. He says he later found some samples and the data from them were wrong, but he couldn’t tell Cho and was “afraid of because the data were presented to our collaborators and others.”

Han says he hoped or expected tests on other samples would find neutralizing activity, so he continued the ruse to cover the error. “In order to show neutralizing activity continuously I added the human sera with a neutralizing activity to the second samples” sent to another lab. Han claims he “falsified only samples that showed some [neutralizing] activity because I wanted them to look better.”

Spiking samples to create a positive result where there was little or none is unusual, but Han also admitted to more common research misconduct: modifying data. In the report, Charlotte Bronson, ISU associate vice president for research and the university’s research integrity officer (RIO, not be confused with ORI), says she compared lab experiment data (found on a Dell computer used to control the test instrument) with spreadsheets Han gave to another researcher in Cho’s lab.

“The comparison showed that digits were changed in the data in the … spreadsheet to make samples that had little or no neutralizing activity appear to have high activity, thus confirming that (Han) had falsified data” by manipulating the files.

The report includes spreadsheets of data from tests ISU ordered to check for the presence of human antibodies – specifically immunoglobulin G (IgG) – in rabbit blood samples. “Results showed all tested samples showing potent neutralizing activity were spiked with human IgG,” Bronson wrote.

In my next post (this one is long enough) I’ll go into the details of the investigation, how Bronson and Cho apparently attached Han to the misconduct, and some of the ramifications.

In the meantime, if you care to wade through the ISU report (or even if you don’t), it’s helpful to understand something about the research in question.

Cho’s group was trying to invoke an immune response to key glycoproteins (proteins with attached carbohydrate groups, abbreviated as gp) found on HIV’s outer membrane, or envelope. Their vaccine candidates are made from gp120, gp41 and a gp41 segment labeled gp41-54Q.

If the ISU team’s vaccines are successful, the body would develop antibodies to these proteins that also would attack the virus itself, warding off HIV infection.

Of course, it’s still far from sure this will work. The abstract for one of the talks (see page 23 in the link) Cho delivered based on the faked results notes that eliciting broadly neutralizing antibodies (abbreviated variously as BR-Nabs, NAbs, Abs or bnAbs) is a major roadblock to developing an AIDS vaccine. While a particular piece of gp41 is an attractive target for vaccine development, many past attempts have failed, the abstract says. (None of the faked data was published as a full-blown journal article.)

That’s why the abstract touts the results – later revealed to be false – as “a significant breakthrough” that “opens up a new avenue of AIDS vaccine research.” It’s no wonder the results got the attention of scientists at the National Institutes of Health and helped ISU garner least one additional research grant.

But it would be a shame if this incident completely discredits Cho’s research. His group appears to be doing some really interesting work, especially engineering Lactobacillus to express HIV glycoprotein. The idea is to inoculate humans with this bacterium, which is one of the billions of benign and beneficial bugs in the human body (and in cheese). The altered Lactobacillus would produce the glycoprotein segments, setting off an immune response that also would kill HIV. Cho is touting the approach as a possible way to immunize against other diseases, too.

Will it work? Han tried to make it appear it was. Some of the data he changed in files of neutralization experiments made it look like the engineered Lactobacillus triggered broadly neutralizing antibodies in rabbits.

[…] to Han’s misconduct (which he admitted to), examined whether there are criminal implications, and delved into Han’s possible […]

[…] more background, read my other posts here, here and […]